Dealers in art and antiquities have long been part of money laundering typologies on a global scale, given the illegal movement of funds flowing through these channels. Recent efforts to provide greater scrutiny to detect and prevent laundering money through art and antiquities are bringing newfound attention that financial institutions should consider as they run their Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism Programs (AML/CFT Programs).

The Problem of Money Laundering Using Art and Antiquities

The world of art and antiquities trading is widely portrayed as a glamorous hobby reserved for the rich and famous. The fact that this market has been loosely regulated in the United States leaves the industry open to illegal actors in the dark market and open trade, such as auction houses and the internet. It is an attractive method for layering illicit funds into the financial system by buying and selling high-end items.

Money laundering through art and antiquities is a known method of hiding illicit funds. According to estimates from The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), billions of dollars are laundered through the global art market annually, with further billions estimated to pass through the underground art market each year. Methods of illegal transactions include theft, fakes, illegal imports, and organized looting. Furthermore, terrorist groups have generated revenue via trafficking antiquities.

Why Money Laundering Through Art and Antiquities is a Risk

Several factors contribute to the ease and attraction of money laundering using art and antiquities:

- Anonymity: Sales and purchases can easily be accomplished anonymously, even with reputable auction houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s. There are various reasons why legitimate transactions are made anonymously, such as privacy expectations and not wanting to draw public attention to the transactions. In addition, a more strategic fact is that there is power in anonymity.

- Fluctuating valuation: Another aspect of the art and antiquities trade making it prone to money laundering is that it is difficult to place a value on these high-end items as the worth is based on the eye of the collector – the purchaser. The pricing of art and antiquities is a highly subjective practice allowing criminals to launder vast sums of money, mainly through art auctions.

- Absence of requirements to report large cash transactions: Art dealers can keep the names of buyers and sellers anonymous. And unlike U.S. businesses that deal in large sums of money and must file currency transaction reports (CTRs) and suspicious activity reports (SARs), art dealers do not have to file reports with FinCEN. Examples of exorbitant amounts paid under anonymity for these items through legitimate auction houses are:

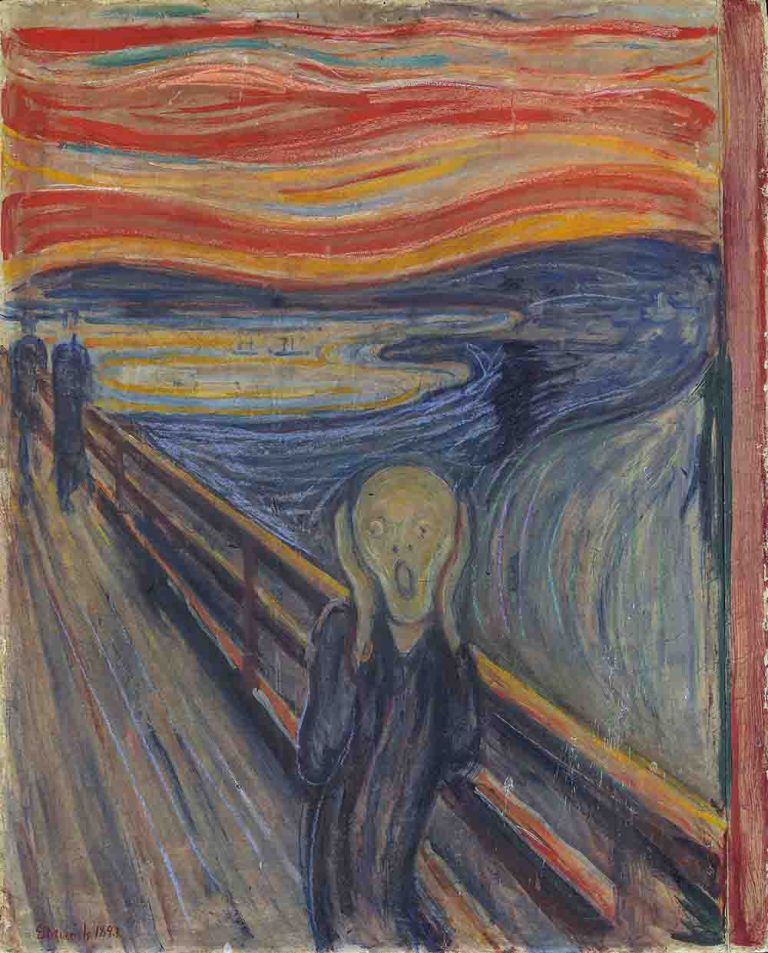

- Sotheby’s $120 million sale of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” set a 2012 record for the most expensive work sold at auction. The identity of the buyer was allowed to be kept unknown for some time. Speculation on the purchaser before he was identified had included Russian oligarchs.

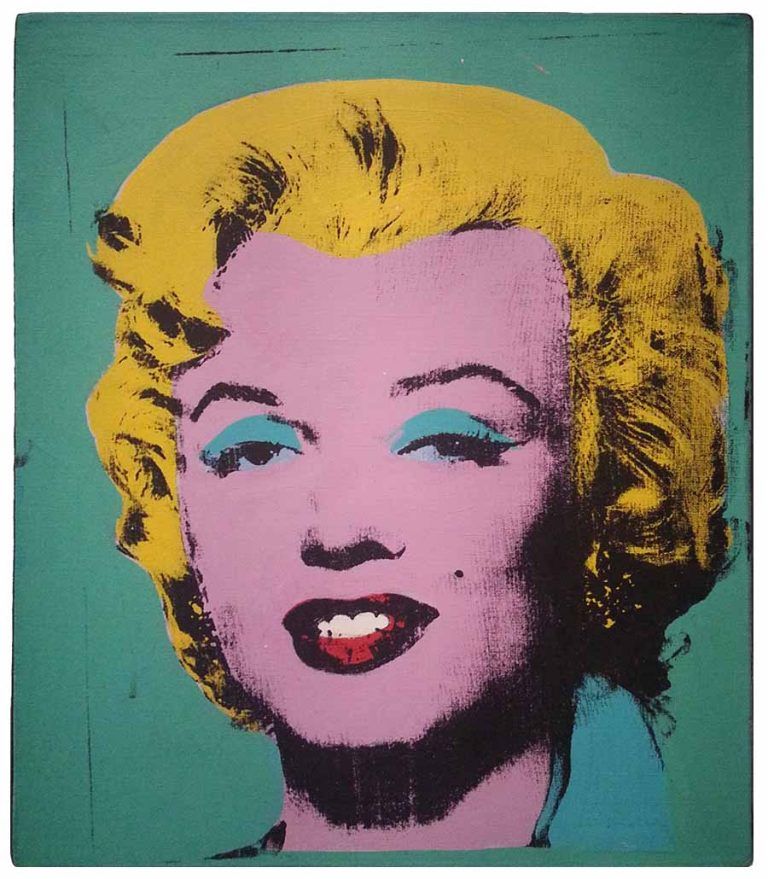

- In 2022, Christie’s sold Andy Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe, “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,” for $195 million, setting a new record. The purchaser was an art dealer, but the eventual owner is unknown.

- Picasso’s “Green Leaves, Nude and Bust,” which for two years was the world’s top-priced work at auction after Christie’s sold it for $106.5 million, is currently on display at London’s Tate Modern, where its owner is still not identified.

The anonymity afforded to purchasers and sellers of high-end collectibles, along with the large sums for which art and antiquities can change hands, have proven to be enticing to money launderers and kleptocrats.

Edvard Munch “The Scream” | Photo stock.adobe.com

Andy Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe, “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,” Photo 215104290 / Marilyn Monroe © Gustavo Rosa | Dreamstime.com

Recent Study Outlines How Art is Used for Money Laundering

Congress attempted to address loopholes that might promote antiquities and art money laundering by passing the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA). In a proposed rule issued by FinCEN in September 2021, antiquities dealers would be brought under the same AML regulatory framework previously applied to U.S. financial institutions under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). Industry leaders expect the final rule to be published in the near future.

AMLA also mandated that the Treasury Department study the high-end art industry to determine the degree of money laundering and terror financing risk associated with art dealers. This study determined that money laundering does occur through the sale and purchase of high-end art. It noted the following three ways criminals are using art to launder money:

- Accepting art as payment to integrate illicitly generated or acquired funds into the financial system;

- Hiding or parking the proceeds of illegal activities via art purchases; and

- Using art purchased with illicit proceeds as collateral for other transactions to disguise the source of funds.

Despite these findings, Treasury concluded that the risk of money laundering via art was not significant enough for art dealers to be brought under the definition of the BSA at this time. Greater priorities for closing loopholes were mentioned, such as:

- The beneficial ownership registry mandated by the Corporate Transparency Act, and

- Deterring money laundering and public corruption occurring via high-end real estate.

Scott Rembrandt, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Strategic Policy in the Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes, said that further regulations for art dealers are not required until “we’ve tackled more systemic issues, like creating a beneficial ownership registry to crack down on shell companies.”

Efforts to Combat Money Laundering Through Art and Antiquities

It’s important to note that much of the requirements of AMLA are to be created and implemented by FinCEN, a small division of the U.S. Treasury already struggling with a lack of funding and other resources. The Biden administration officials are asking Congress to send $210 million to FinCEN under the U.S. government’s proposed 2023 budget, which marks a roughly 30% increase from its current funding. While this indicates that FinCEN is underfunded, the budget is not expected to have bipartisan support.

FinCEN Issued an Advisory on Kleptocracy and Foreign Public Corruption in April of 2022, urging financial institutions to focus efforts on detecting the proceeds of public corruption. The advisory emphasizes that corrupt public officials launder their illicit profits through various means, including shell companies or by purchasing high-end assets, such as real estate, yachts, private jets, and high-value art. Was this an afterthought after the study postponed what might have been another loophole closed to money launderers as other countries have done?

The lack of U.S. legislation and oversight has promoted the U.S. to the number one money laundering country globally, with shell companies used to purchase high-end collectibles and cultural properties. As criticism continues from global watchdog organizations such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), concerns have increased since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. With Russian sanctions implemented worldwide, oligarchs and other kleptocrats have seized loopholes and are hiding assets into high-end purchases, including art and antiquities. A lack of regulatory oversight could lead to serious national security issues.

Financial Institution Action to Detect and Prevent Money Laundering Art and Antiquities

In the meantime, what should financial institutions do to ensure that money laundering through art and antiquities is not occurring through their bank? It is never too early to bump up your knowledge in these areas and prepare for regulations surrounding antiquities dealers. Although antiquities is positioned to be included under the BSA with all of the monitoring and reporting requirement that entails, it would be prudent for financial institutions to apply the exact same requirements to art dealers, including:

- Both art and antiquities dealers in your enterprise-wide risk assessment

- Recognizing that art and antiquities dealers, and customers who use them, are at higher risk for money laundering, terrorist financing, and political corruption

- Creating processes and procedures for enhanced due diligence for art and antiquities trading

- Applying beneficial ownership requirements to any shell corporations, including those dealing in high-end art

- Submitting suspicious activity reports for any large cash purchases with unknown sources of funds

FinCEN issued a notice in March 2021 informing financial institutions of efforts related to trade in antiquities and art. The notice includes clear expectations for SAR filing if suspicious activity is detected in these areas. Having proactive procedures in place to detect money laundering in art and antiquities will prepare you for what is sure to be further regulations around art dealers. It will also show your banking regulators that you understand your risk related to both antiquities and the art communities.

Terri Luttrell, Compliance & Engagement Director with Abrigo (formerly Banker’s Toolbox), is CAMS-Audit certified and has over 20 years in the banking industry, working both in medium and large community banks in the areas of compliance/fraud, commercial lending, and deposit operations. As an AML consultant, she has helped institutions develop BSA/OFAC programs to ensure all regulatory requirements are met, and managed a team of AML investigators for a large/cross-border institution, among other roles.